Highlights

- Simultaneous LDLT-SG allows a semi-elective option for patients with obesity with MASH cirrhosis who do not have a MELD score competitive for a DDLT.

- Simultaneous LDLT-SG is safe and results substantial, sustained weight loss.

- Simultaneous LDLT-SG also results in decrease in metabolic comorbidities and likely long-term graft steatosis.

Abstract

Background: Increasing obesity and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) cirrhosis present challenges in liver transplantation.

Objectives: While simultaneous sleeve gastrectomy (SG) has been described in the deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT) population, its role in living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) remains poorly unexplored.

Setting: Simultaneous SG and LDLT for obese patients with MASH cirrhosis.

Methods: This is a pilot study of LDLT recipients who underwent simultaneous sleeve gastrectomy (LDLT-SG) at this institution from December 2023 to May 2025. Short term postoperative outcomes, weight loss, graft function, and metabolic syndrome comorbidities were compared to a matched LDLT-only cohort at this institution along with a DDLT-SG cohort at another institution.

Results: Seven patients with a body mass index (BMI) of 42.1 (standard deviation [SD] 5.8) underwent simultaneous LDLT-SG. They had MASH cirrhosis with an average model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score of 18.6 (SD 7.7). Patients experienced significant total body weight loss (TBWL%): 15.7% at 1 month, 26.5% at 6 months, and 31.3% at 12 months. Excess body weight loss (EBWL%) was 42.2%, 71.9%, and 81.3% at the respective intervals. No biliary or vascular complications noted post-operatively. Three patients were re-admitted – 2 for PO intolerance and 1 for a gastric sleeve leak. 57% of patients noted resolution of obesity-related comorbidities. Postop magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) assessments indicated healthy liver grafts.

Conclusion: Simultaneous LDLT-SG allows a semi-elective option for patients with obesity and MASH cirrhosis who have decreased access to DDLT. The combined procedure promotes substantial weight loss, improved metabolic comorbidities and likely decreased graft steatosis. Early outcomes are promising and suggest SG offers risk reduction in the setting of LDLT. (Surg Obes Relat Dis 2025;■:1–9.) © 2025 American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights are reserved, including those for text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MESH) cirrhosis is the second most common indication for liver transplant in the United States and is projected to overtake alcohol associated liver disease (AALD) in the coming decades as the obesity epidemic continues [1–4]. Patients undergoing liver transplantation due to MASH are at high risk for disease recurrence. Hepatic steatosis can recur in .50% of those transplanted for MASH cirrhosis and MASH has been noted in up to 38% at . 5 years post-transplant [3,5]. Patients transplanted for MASH cirrhosis continue to be at risk for metabolic syndrome complications secondary to diabetes, hypertension, sleep apnea, and hyperlipidemia [5].

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) suggests that sleeve gastrectomy (SG) is the optimal bariatric procedure for patients with cirrhosis due to its preservation of endoscopic access to the stomach and biliary tree along with its avoidance of malabsorption, which is beneficial in the context of cirrhosis [6]. Simultaneous liver transplant and sleeve gastrectomy (LT-SG) has been described in the deceased donor liver transplantation population as an effective means to achieve weight loss and improved metabolic outcomes without increased risk of liver allograft rejection [7–10]. Deceased donor liver transplant along with a sleeve gastrectomy has been noted to be superior to medical weight loss in reducing post-transplant metabolic complications including diabetes, insulin resistance, hypertension and recurrent metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) [10,11]. A 2023 systematic review assessed the timing of metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS) in liver transplant patients; the authors showcased that simultaneous LT-SG was associated with lower morbidity and mortality than MBS performed after transplant [12].

Simultaneous MBS, specifically sleeve gastrectomy, has been poorly studied in the living donor liver transplant (LDLT) recipient population. Singhal et al. previously published a case series of 2 patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy several months after LDLT [13]. This year, in a series of 72 patients, Larson et al. reported one patient who underwent a simultaneous LDLT-SG [14]. Simultaneous LDLT-SG allows a semi-elective option for patients with obesity and MASH cirrhosis who have a MELD score that is not competitive for a deceased donor liver transplant (DDLT). This is the first published case series to describe outcomes for patients who underwent simultaneous LDLT-SG.

Methods

This pilot study involved patients who underwent simultaneous LDLT-SG at University Hospital in San Antonio from December 2023 to May 2025. This process was made possible through a multidisciplinary collaboration between the division of metabolic and bariatric surgery and the division of transplant surgery. Patients were identified and data were extracted from the electronic patient database. This study was approved by the institutional review board at University Hospital and University of Texas Health San Antonio, and patients consented to participation in outcomes studies during the informed consent prior to their surgery.

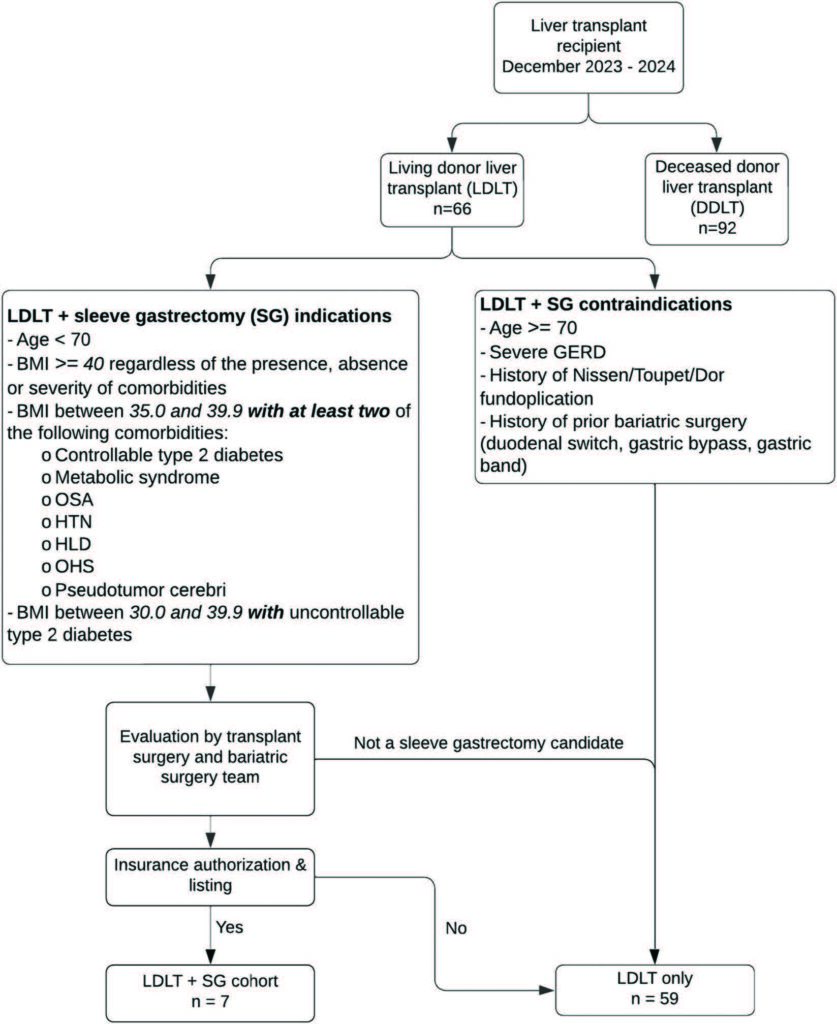

Patients evaluated for a simultaneous LDLT-SG had to meet the criteria noted in Figure 1. LDLT-SG was contraindicated in patients who were ≥70 years, had severe Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, had a history of Nissen, Toupet or Dor fundoplication, and a history of prior MBS including duodenal switch, gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and gastric band. There was no maximum patient body mass index (BMI) for the procedure, and each patient was reviewed on a case-by-case basis. If a patient met the inclusion criteria, the preliver coordinator provided the patient initial education about the possibility of a simultaneous procedure. The patient then underwent simultaneous transplant and MBS evaluation followed by insurance authorization. Next, the patient would be discussed in liver selection committee and then be scheduled for surgery. The elective nature of LDLT makes planning a simultaneous operation easier.

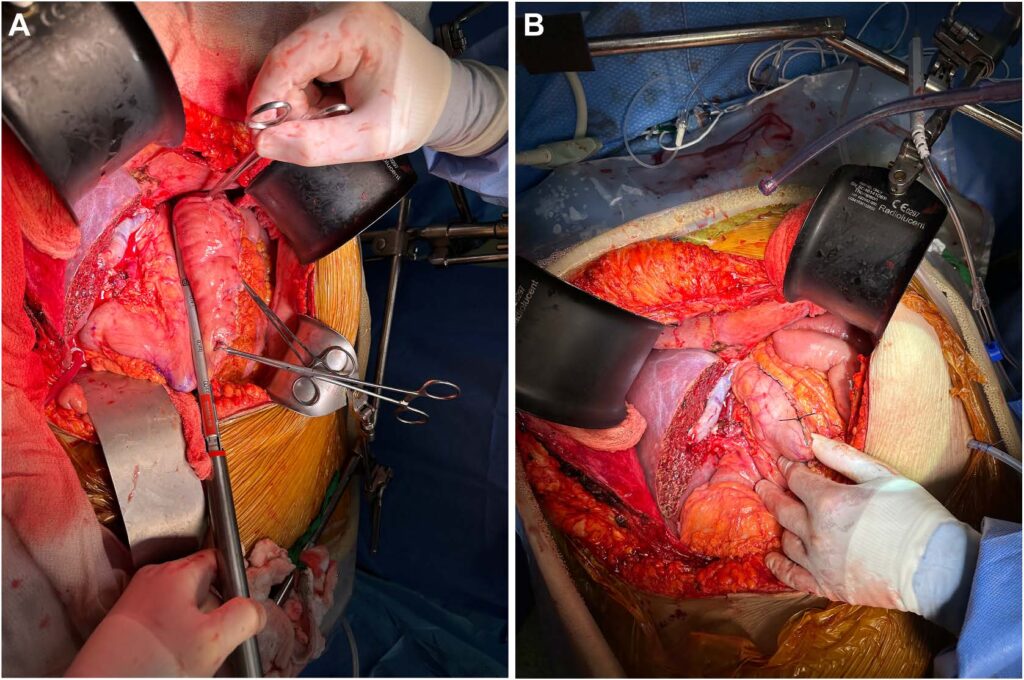

Operative technique

Since these cases involved a LDLT, the first operation was a living donor right hepatectomy to procure the right hepatic graft. Following this, the recipient was taken back to the operating room and a hepatectomy was performed. Then, the donor graft was modified in the back table. Next, the graft outflow anastomoses were performed followed by the inflow anastomoses to the right portal vein and right hepatic artery. Once the vascular anastomoses were complete and the liver graft was reperfused, the MBS team joined the operation. The MBS team mobilized the greater curvature of the stomach all the way to the level of the left crus of the diaphragm using a vessel sealer device. The stomach was decompressed at this time, the orogastric tube was removed and a 40 Fr blunt tip bougie was inserted into the stomach. Then, an open sleeve gastrectomy was performed using a single fire stapler (Titan SGS stapler – Teleflex/Standard Bariatrics) or a sequential fire stapler (Signia with Tri-Staple – Medtronic USA) [15]. This can be noted in Figure 2. Over time, the MBS team also began suturing the greater curvature of the gastric sleeve to the greater curvature mesentery or omentum, in-order to prevent the sleeve from rotating and adhering to the cut edge of the liver graft. An intraoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed to visualize the staple line within the gastric sleeve lumen. Notably, the sleeve creation portion of the operation adds no extra time to the surgery, as the protocol in our institution is to allow for an hour for the liver graft to perfuse and correct coagulopathy prior to performing the biliary anastomosis. Finally, the biliary anastomosis was performed before abdominal wall closure (Fig. 2).

Postoperative protocol

The nursing staff, pharmacy, and dietician team on the floor were educated about the postop expectation for these patients prior to the start of this series. After extubation, the patients were started on a stage 1 bariatric diet. Once they had tolerated 4 ounces for 4 consecutive hours, they were advanced to a stage 2 bariatric diet, which they would continue for 2 weeks after surgery. Patients were to receive oral suspension forms of daily bariatric multivitamins and proton pump inhibitors. In terms of their transplant-related medications, they were cleared for pills ,10 mm; everything else was delivered in a suspension form. Patients followed the center’s standard post liver transplant protocol otherwise. They were followed outpatient by transplant surgery, MBS, hepatology, and dietician teams.

A comprehensive literature review was performed to compile studies that reported outcomes for simultaneous DDLT and sleeve gastrectomy. A similar search was performed for LDLT and sleeve gastrectomy. A demographics table was compiled comparing the LDLT-SG cohort, a matched LDLT-only cohort from this institution along with a DDLT-SG cohort from another institution (Zamora-Valdes et al.) [10]. Short term post-operative outcomes [vascular, biliary, and bariatric complications; acute kidney injury (AKI) (based on RIFLE criteria)], graft function (based on liver function tests and hepatology evaluation), length of stay, readmissions (and their causes), and weight at 1-month, 6 months, and 1 year were noted [16]. Presence of obesity related comorbidities were quantified based on dependence on diabetes and hypertension medications, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) symptoms and lipid panel (hyperlipidemia) results. Magnetic resonance imaging proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF) at 6 or 12 months were obtained to quantify fat fraction within the patient’s graft. The percent of total body weight loss (TBWL%) of this cohort of simultaneous LDLT-SG patients was compared to a matched cohort of patients with MASH cirrhosis, a similar MELD score, and BMI . 35 who underwent LDLT only. Since our program hasn’t performed a significant number of simultaneous DDLT- SG, published outcomes from another institution (Zamora-Valdes et al.) were used as a comparison group [10]. Statistical analysis was performed using a t-test and ANOV A for continuous variables. Data are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). SPSS software (IBM SPSS Inc) was used for analysis.

Table 1

Publications on outcomes of simultaneous sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and deceased donor liver transplant (DDLT) or living donor liver transplant (LDLT) 1 SG

| Author | Y | Country | Timing of SG | Number of patients | Multicenter (Y/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heimbach et al. [17] | 2013 | USA | Simultaneous DDLT | 7 | N |

| Nesher et al. [22] | 2017 | Israel | Simultaneous DDLT | 3 | N |

| Zamora-Valdes et al. [10] | 2018 | USA | Simultaneous DDLT | 25 (14 SLK) | N |

| Wijarnpreecha et al. [21] | 2020 | USA | Simultaneous DDLT | 49 | Y |

| Yemini et al. [20] | 2021 | Israel | Simultaneous DDLT | 3 | N |

| Singhal et al. [13] | 2021 | India | After LDLT | 2 | N |

| Fernandes et al. [18] | 2022 | Brazil | Simultaneous DDLT | 7 | N |

| Gunturu et al. [19] | 2022 | USA | Simultaneous DDLT | 10 | N |

| Tariq et al. [23] | 2023 | USA | Simultaneous DDLT | 14 | N |

| Manzia et al. [9] | 2025 | Italy | Simultaneous DDLT | 11 | N |

| Larson et al. [14] | 2025 | USA | Simultaneous DDLT | 71 | Y |

| Simultaneous LDLT | 1 |

Results

A systematic literature review resulted in 10 studies that involved simultaneous DDLT and sleeve gastrectomy as noted in Table 1 [9,10,14,17–23]. There are multiple studies that review outcomes of patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy before or after DDLT, but these were out of the scope of this manuscript. One case series involved LDLT and sleeve gastrectomy; in this study, the 2 SGs occurred one patient who underwent simultaneous LDLT-SG.

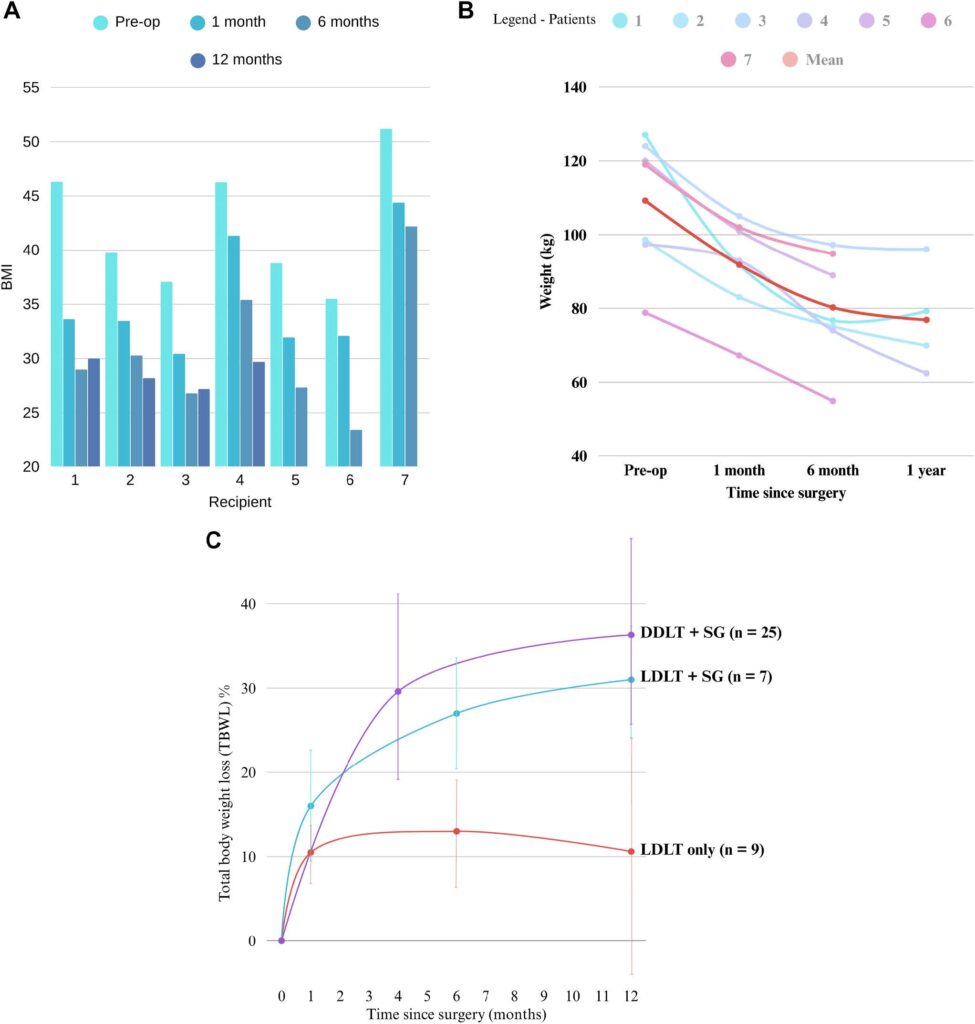

In this study, 7 patients with a mean preoperative BMI of 42.1 (SD 5.8) underwent a simultaneous LDLT-SG. All patients had a component of MASH cirrhosis with an average MELD at transplant of 18.6 (SD 7.7) (Table 2). The LDLT-SG cohort had a lower MELD at transplant compared to the DDLT-SG cohort from the outside institution (Table 2). The mean excess body weight loss percent (EBWL%) was 42.2% (618.1) at 1 month, 71.9% (620.8) at 6 months, and 81.3% (67.4) at 1 year. Figures 3A and 3B showcase change in BMI and weight after LDLT-SG.

The matched cohort of LDLT-only patients had 9 recipients while the DDLT-SG cohort (after removing 4 patients who underwent also underwent a kidney transplant) from the outside institution had 25 patients (Table 2). Patients who underwent simultaneous LDLT-SG had a sustained weight loss response at 1 year and they had greater TBWL% at 1 (15.5 vs. 10.5, P 5 .04), 6 (26.5 vs. 13, P , .001) and 12 months (31.3 vs. 10.6, P , .001) postsurgery compared to the LDLT-only cohort (Fig. 3C). There was no significant difference in TBWL% at 1 year between the DDLT-SG and the LDLT-SG groups (36.3 6 12.0 vs. 31.3 6 6.9, P 5 NS). There were no postoperative biliary complications, vascular complications or deaths during this period (Table 3). Of note, graft function of the sleeve cohort was similar to the nonsleeve LDLT cohort. Two patients had re-admissions secondary to oral feeding intolerance. One patient was re-admitted with a contained distal staple line gastric sleeve leak 1 month after her operation; she required interventional radiology and advanced endoscopy interventions with wide drainage to help resolve this leak. Five of 7 (71%) developed an AKI postop with eventual resolution of AKI. Mean postoperative length of stay was 9.6 days (SD 4.3).

Table 2

Demographics

| LDLT + SG N = 7 | LDLT only (matched) N = 9 | DDLT + SG N = 25 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex (%) | 71% | 88% | 60% |

| Age at listing | 57.1 (10.2) | 60.7 (4.8) | 53.6 (5.8) |

| MASH cirrhosis etiology | 100% | 100% | 80% |

| Weight at transplant (kg) | 109.2 (17.9) | 94.9 (10.3) | 134.8 (25.0) |

| BMI at transplant | 42.1 (5.8) | 37.5 (1.7) | 46.5 (5.9) |

| MELD at transplant | 18.6 (7.7) | 17 (4.9) | 32.6 (7.0) |

The matched cohort of LDLT only patients had no resolution of their metabolic syndrome comorbidities. 4/7 (57%) patients had resolution of at least one obesity associated comorbidity at 6 months post-LDLT-SG (Table 4). At 6 months post-op, 50% of the patients with preoperative hypertension were off anti-hypertension medications and 50% of patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) were off diabetes medications. Both patients diagnosed with OSA prior to surgery had resolution of their symptoms at 6 months. At 6 months, hyperlipidemia (HLD) improved but did not resolve for any of the 3 patients with HLD. Of the 5 patients who had a post-op MRI done, all of them had no signs of recurrent hepatic steatosis in the graft. 80% of their MRI FFs were less than 6.5%, suggesting a normal, non-fatty liver; only one patient had a MRI FF of 7.1% suggesting mild hepatic steatosis.

Discussion

This is the first published case series to describe outcomes for patients who underwent simultaneous LDLT and SG. This is a novel treatment modality for patients undergoing liver transplantation due to MASH cirrhosis as they are at high risk for disease recurrence in the transplanted graft [5]. This cohort showed substantial and sustained weight loss at 1 year. Moreover, 57% of patients had resolution of metabolic disease comorbidities post-transplant, unlike the matched cohort.

Table 3

Surgical outcomes

| Pt | Graft function (6mo) | Vascular complications | Biliary complications | Bariatric complications | Postop AKI (Y/N) | AKI resolution (Y/N) (1mo) | Postop length of stay | Re-admissions in first 6 mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Good | None | None | None | Y | Y | 10 | No |

| 2 | Good | None | None | None | Y | Y | 8 | Yes 1 – 3 wk postop for neurotoxicity secondary to Tacrolimus 2 – 3 mo postop – Atrial flutter requiring cardioversion |

| 3 | Good | None | None | None | N | NA | 9 | No |

| 4 | Good | None | None | PO intolerance | Y | Y | 19 | Yes (4 mo postop PO intolerance, Clostridium Difficilie and E- coli bacteremia 2/2 abdominal fluid collection) |

| 5 | Good | None | None | None | Y | Y | 7 | No |

| 6 | Good | None | None | PO intolerance | N | NA | 7 | Yes (5 mo postop for PO intolerance) |

| 7 | Good | None | None | Gastric sleeve leak (distal) | Y | N | 7 | Yes 1 – 3 wk postop – shortness of breath 2 – 4 wk postop – contained, distal gastric sleeve leak |

This LDLT-SG cohort had similar sustained weight loss outcomes to their DDLT-SG counterparts in prior studies [7–10]. Mean TBWL% at 6 months was 26.5% (SD 6.6) and at 12 months was 31.3% (SD 6.9). This is similar to the 36% (SD 12) weight loss noted at 1 year by Zamora-Valdes et al. in their DDLT-SG cohort and 30.2% TBWL% at 1 year by Larson et al. in their multi-center study of 72 patients [10,14]. The mean excess body weight loss percent (EBWL%) was 42.2% at 1 month, 71.9% at 6 months, and 81.3% at 1 year. In comparison, Lin et al.’s DDLT-SG cohort had a EBWL% of 16.4% at 1 month, 55.5% at 6 months and 65.4% at 12 months [24]. 4/5 (80%) patients who had an MRI of their liver graft at least 6 months after surgery had non-fatty livers (MRI FF , 6.5%) without any signs of steatosis, while one had mild hepatic steatosis (MRI FF – 7.1%). MASH recurrence in post-liver transplant patients is published at 18% to 38% [3,4]. Their underlying metabolic syndrome isn’t treated by transplantation alone, hence patients with MASH cirrhosis need a more nuanced approach to management. 57% of patients in this cohort had the resolution of at least one metabolic syndrome comorbidity at 6 months post-transplant. Sleeve gastrectomy is known to decrease the rate of metabolic syndrome by 53% to 85% at 1 year with sustained improvements in the long-term [25,26]. The LDLT-SG cohort reflects this trend. In fact, the patients in this series likely wouldn’t have been considered for LDLT alone without aggressive pre-operative weight loss. Patients with obesity who undergo liver transplant have a higher rate of mortality secondary to cardiovascular events, which is likely secondary to their metabolic syndrome comorbidities [27]. We hypothesize that these patients will show a mortality benefit in the long-term from the resolution of these comorbidities.

Simultaneous LDLT-SG offers a semi-elective option for patients with obesity and MASH cirrhosis who have decreased access to DDLT. It allows for a single operation and recovery for the patient while addressing the underlying cause of their metabolic syndrome and cirrhosis. Furthermore, it allows for a scheduled, day-time surgery and eases coordination logistics between the MBS and transplant surgery teams. The simultaneous procedure is also advantageous because it allows for the patient to have their transplant and weight-loss operations before they decompensate further and become sicker from a MELD score perspective; this in-turn allows the sleeve gastrectomy to be done while the patient is in a healthier state. Notably, the sleeve creation portion of the operation adds no extra time to the surgery, as the protocol in our institution is to allow for an hour for the liver graft to perfuse and correct coagulopathy prior to performing the biliary anastomosis. The disadvantage of simultaneous surgery is the potential for increased complications in the short term. Moreover, patients may find it challenging to adapt to the significant changes that result from 2 major operations. These patients not only have to adapt to whole new set of immunosuppressive medications, but they must also modify their diet and lifestyle.

Simultaneous LDLT-SG is not without complications. The final patient in this series had a contained distal gastric sleeve staple-line leak 1 month after her surgery. Imaging noted the sleeved stomach taking a sharp turn after the incisura secondary to adhesions to the cut edge of the transplanted liver. She required multi-disciplinary management with the help of interventional radiology (IR) and the advanced endoscopy (AE) team; at first, she had an IR drain placed in the contained perforation, followed by an internal double pigtail stent across the sleeve leak, which was downsized over time as the leak healed. The patient also had a naso-jejunal dobhoff tube placed by the AE team for distal feeding access. Staple line leaks are a feared complication of sleeve gastrectomy and typically occur just below the level of the gastroesophageal junction. Leak rates reported in the literature range between 1.7% and 4.9% of cases and distal gastric sleeve staple line leaks are exceedingly uncommon [28]. Two patients required re-admissions for PO intolerance. One of them had a diagnostic laparoscopy performed, but the anatomy of their sleeve was not deemed to be the cause of the of their PO intolerance. Their symptoms have improved since.

Table 4

Comorbidity resolution

| Pt | Preop DM | Preop HTM | Preop OSA | Preop HLD | 6mo after DM | 6mo after HTM | 6mo after OSA | 6mo after HLD | A1c @ 6mo | MRI FF @ 1yr | Comorbidity resolution @ 6mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | 4.8 | 2.5 | Y |

| 2 | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | 4.7 | 2.3 | N |

| 3 | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | 5.4 | 7.1 | Y |

| 4 | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | 5.1 | 0.3 | N |

| 5 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | 6.6 | 0* | Y |

| 6 | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | 5.4 | N | |

| 7 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | 5.2 | Y |

Other logistical challenges include obtaining insurance coverage for a simultaneous LDLT-SG. Since this modality is not widely used, it was not covered by many insurance providers and required the hospital to take on costs of the procedure, which may not be sustainable in the long-term. A potential solution is an earlier referral to the MBS team. This will have to be addressed at the administrative level to provide access to this novel therapy to MASH cirrhosis patients with obesity. Patients with MASH cirrhosis will also benefit from coaching by a dietician along with medication for weight-loss in the perioperative setting. Moving forward, we hope to provide this option to all our MASH cirrhosis patients who meet criteria for LDLT-SG.

This manuscript has its limitations. Firstly, it’s a feasibility study with a small cohort and small matched comparison group, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Due to the novelty of the procedure, only short-term postoperative outcomes are available so far. Future studies will need to focus on long-term outcomes of LDLT-SG patients and ideally a larger cohort as well. A multi-institutional trial is also warranted to demonstrate the broader feasibility of these results. Furthermore, since LDLT is such a niche operation in the United States, further expansion of LDLT is needed to make this combined operation a viable option for patients nationwide [29].

Conclusion

Simultaneous SG in LDLT patients allows a semi-elective option for obese patients with MASH cirrhosis who have decreased access to deceased donor transplantation. The combined procedure provides benefits in sustained weight loss, reduction of obesity related comorbidities, and likely decreased long-term graft steatosis. Very early outcomes are promising since bariatric surgery offers risk reduction in the setting of transplant.

Disclosures

Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kempenich have consulted for Teleflex/Standard Bariatrics and Intuitive surgical and have received an honorarium from them. Dr. Peterson and Van Sickle have also consulted for Medtronic.